Spirality vegetative - phyllotaxis („parastichy numbers")

Spiral Developmental Patterns in the Stem and Inflorescence of Lilium tigrinum

That shot clearly shows the "fibonacci spirals" (two intersecting spiral lines - one shallow one, and the other much steeper) which allow for the plant head to grow without rupturing open along a single weak line. There has been much written about the mathematical relationships of the number of segments in these intersecting lines… bract-bracteole spirals reversed the spiral of vegetative leaves [1]

The letter with curious address forwarded by Mrs Hooker was from a German Homœopathic Doctor—an ardent admirer of the Origin—had himself published nearly the same sort of book, but goes much deeper—explains the origin of plants & animals on the principles of Homœopathy or by the Law of Spirality— Book fell dead in Germany— Therefore would I translate it & publish it in England &c &c

(The German homeopathic doctor has not been identified. He was seemingly an adherent of Johann Wolfgang von Goethe’s law of spiral growth of plants. Goethe[2] claimed in his paper, `[there is in plants a general spiral tendency, through which, in connection with a vertical tendency, every construction, every form of plant following the law of metamorphoses is achieved]‘ (Goethes Werke pt 2, 7: 49).[3]

- plant with spiral phyllotaxis

Phyllotaxis is the study of plant patterns. Despite their diversity similar patterns are found in many different types of plants. Naturally this is due to the fact that many plants follow the same pathways during their early stages of development. A common eye catching pattern consists of two sets of spirals forming a lattice. This can be seen in the stamens of flowers (e.g. the male Leucadendron Discolor shown at the right), the florets of compound flowers (e.g. the Calendula shown below), the scales of pine cones, cycads, and seed ferns. This pattern is known as Spiral Phyllotaxis

At the tip of a plant shoot are meristematic tissues, i.e. regions containing undifferentiated cells. These meristems are responsible for the production of the plant's organs such as leaves, thorns, tendrils, sepals, petals, etc. Near the boundary of the meristem is a region called the apical ring. Its in this region that new plant organs are formed. It usually takes a microscope to observe the process. Plant organs begin when cells in a spot along the apical ring undergo extensive cell divisions resulting in a bump, called a primordium, on the side of the apical ring. The phyllotactic pattern exhibited by the primordia is preserved as they develop into the various plant organs. Therefore with a good model of meristematic development we can account for the phyllotactic patterns found in nature.

Around the turn of the 18th century the well known Astronomer Johannes Kepler observed that the Fibonacci numbers are common in plants. And around 1790 Bonnet pointed out that in spiral phyllotaxis the number of spirals going clockwise and counter-clockwise were frequently two successive Fibonacci numbers. For example the orange Calendula shown below has 13 spirals going in one direction and 21 spirals going in the other direction.

The Fibonacci numbers are prevalent throughout much of the plant kingdom and understanding why has become a interdisciplinary effort. Several ideas have been proposed over the years. Many of them have been based on the notion that the Fibonacci numbers somehow promote the survival of mature plants. Among the suggestions on how Fibonacci numbers could promote survival are: by providing dense packings of seeds, by allowing circulation of air through leaves, and by allowing light to fall on as many leaves as possible.[4]

Universe of Spiral Lattices

Configurations of points with constant divergence angle are called spiral lattices. In the dynamical model, configurations often converge to very specific spiral lattices: those exhibiting Fibonacci numbers of spirals. A partition of the universe of spiral lattices shows how these Fibonacci lattices lead the way to the Golden Angle.

Many electronic components are available on spools that can be used by machines for counting them out or placing them on boards. These capacitors were once on such a spool, but since we didn't need quite enough for a full spool, they were counted out, rolled up and shipped out to us. They exhibit the opposite spirals of phyllotaxis that are probably most familiar from the face of a sunflower. Who knew capacitors could be so lovely?

elektroničke komponente

Goethe's 1790 Versuch die Metamorphose der Pflanzen presents to Hegel's representations of plant nature. Goethe's essay argues for a view of plant vitality and inner direction operating in and on mechanisms of plant development. Precisely because Goethe's essay revises and critiques the Naturphilosophie account of spirit in nature, he is in one sense Hegel's potential ally. But because Goethe also argues that an inner directed, apparently spiritual dimension of plant development is at work in its mechanical processes, he is also Hegel's necessary antagonist. In his final years Goethe was obsessed by the so-called "spiral tendency". The problem, however, was far from new to him as the versions and variations of curved lines and spirals in Goethe's work clearly show. These forms can actually be found at the crossroads of poetry, visual aesthetics (namely of ornaments), and scientific studies. A crucial point of reference for aesthetics in the later 18th century was William Hogarth's famous concept and model of the "line of beauty" (1753), which also left its traces in Goethe's writings, even in his late period. This study examines his elegy "Amyntas" (1799), the essay "Fossile Bull" (1822), and texts on the metamorphoses of plants and the spiral tendency in vegetation. Spiral forms seem to be so fascinating for Goethe because, with their manifold functions and meanings, they allow us to cross the borders between different genres and disciplines and to connect different kinds of thinking. This transgressive intellectual activity, which we could call 'transdisciplinary', remains a model for important thinkers of the 20th century, such as Paul Valéry, Walter Benjamin or Aby Warburg.[5]

Science of nature has one goal:

To find both manyness and Whole.

Nothing "inside" or "Out There,"

The "outer" world is all "In Here."

This mystery grasp without delay,

This secret always on display.

The true illusion celebrate,

Be joyful in the serious game!

No living thing lives separate:

One and Many are the same.

[Goethe, Epirrhema]

[1] http://www.jstor.org/discover/10.2307/

2440430uid=3738200&uid=2129&uid

=2&uid=70&uid=4&sid=56188932683

[2] The German homeopathic doctor has not been identified. He was seemingly an adherent of Johann Wolfgang von Goethe’s law of spiral growth of plants. Goethe claimed in his paper, `Über die Spiral-Tendenz der Vegetation’: `es walte in der Vegetation eine allgemeine Spiraltendenz, wodurch, in Verbindung mit dem verticalen Streben, aller Bau, jede Bildung der Pflanzen nach dem Gesetze der Metamorphose vollbracht wird.’ [there is in plants a general spiral tendency, through which, in connection with a vertical tendency, every construction, every form of plant following the law of metamorphoses is achieved] (Goethes Werke pt

[3] http://sueyounghistories.com/archives/2008/06/02/johann-wolfgang-von-goethe-and-homeopathy/

[4] http://scotton.freeshell.org/phyllo/

phyllo.html

[5] http://www.scielo.br/scielo.php?pid=S0103-40142010000200013&script=sci_abstract

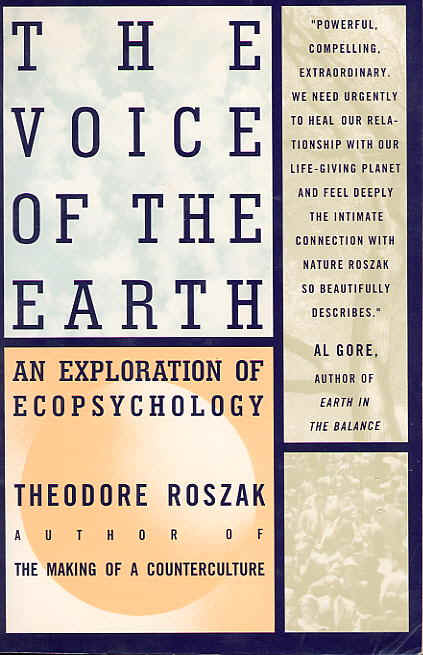

In this startling new book, Theodore Roszak introduces the new field of eco-psychology, which studies the relationship between the individual and the earth. This new brand of psychotherapy defines sanity as the awareness of the connection between the environment and the human soul. By weaving together science, psychiatry, poetry, and politics, Theodore Roszak bridges the gap between the psychological and ecological to explain this new way of thinking about ourselves and our world. This ground-breaking work eloquently explains that if we ignore our connections to the planet, not only the earth but our own mental health will be in jeopardy.

"A bold work, nothing less than a psychoanalysis of civilization.

...Roszak is trying to do for our relationship with the earth what

Freud did for our relationships with each other."

edin.kecanovic

edin.kecanovic irida

irida bglavac

bglavac